For about 18months, an estimate 100 artists crawled their way to an abandoned subway station nearly 4 stories underground to create The Underbelly Project.

A vast new exhibition space opened in New York City this summer, with a show 18 months in the making. On view are works by 103 street artists from around the world, mostly big murals painted directly onto the gallery’s walls.

It is one of the largest shows of such pieces ever mounted in one place, and many of the contributors are significant figures in both the street-art world and the commercial trade that now revolves around it. Its debut might have been expected to draw critics, art dealers and auction-house representatives, not to mention hordes of young fans. But none of them were invited.

In the weeks since, almost no one has seen the show. The gallery, whose existence has been a closely guarded secret, closed on the same night it opened.

Known to its creators and participating artists as the Underbelly Project, the space, where all the show’s artworks remain, defies every norm of the gallery scene. Collectors can’t buy the art. The public can’t see it. And the only people with a chance of stumbling across it are the urban explorers who prowl the city’s hidden infrastructure or employees of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

That’s because the exhibition has been mounted, illegally, in a long-abandoned subway station. The dank, cavernous hall feels a lot farther than it actually is from the bright white rooms of Chelsea’s gallery district. Which is more or less the point: This is an art exhibition that goes to extremes to avoid being part of the art world, and even the world in general.

The show’s curators, street artists themselves, unveiled the project for a single night, leading this reporter on a two-and-a-half hour tour. Determined to protect their secrecy, they offered the tour on condition that no details that might help identify the site be published, not even a description of the equipment they used to get in and out. And since they were (and remain) seriously concerned about the threat of prosecution, they agreed only to the use of street-artist pseudonyms.

Workhorse, in his late 30s, is a well-known street artist with gallery representation; PAC, younger by a decade, is less established but familiar (under a different name) to followers of urban-art blogs. The two came up with the idea for the Underbelly Project in 2008, a few years after PAC first saw the old station, led to it from a functioning one by an urban explorer acquaintance.

Abandoned stations like this — and there are a fair number of them in the city — are irresistible to those who search out hidden spaces in the city, despite or perhaps because of the fact that being there is illegal and potentially dangerous. PAC too found himself compelled after that first visit, and he began going back sporadically.

Art, Underground

Workhorse said he felt that about 90 percent of the art was successful. For this reporter, the most arresting pieces are those that are sinisterly in sync with the Hades-like space, among them skulls, a pair of huge rats and a set of typographical strokes by the British graffiti artist SheOne that resemble the skeletal scratchings of a Lascaux cave painter.

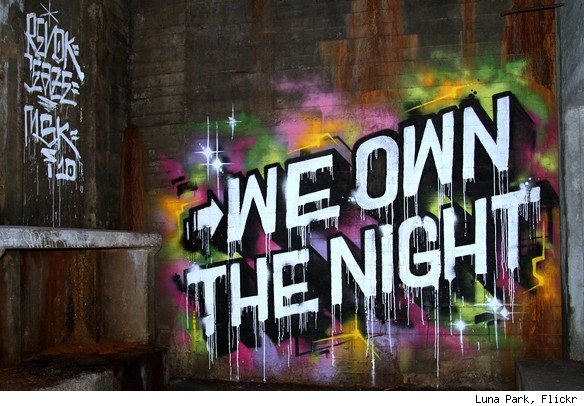

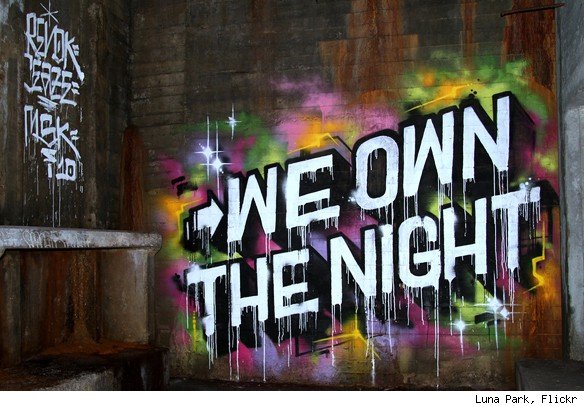

There is a certain amount of anarchic sloganeering and sly digs at the corporate-commercial complex. “WE OWN THE NIGHT,” blares one painting on an end wall. Another, by Mr. English, depicts Mickey Mouse on a respirator.

One installation features a dining table set for two in the middle of a track bed, a relic of a three-course meal served on site by the artist-impresario Jeff Stark to the winner of a competition and her guest. “She wrote an essay about inviting a veteran of the club scene from the early ’90s who was a little out of touch with what younger artists are up in New York these days,” Mr. Stark said. “But he showed up and announced that he was claustrophobic,” so she ended up dining with a friend.

Although other artists’ pieces would seem to be more permanent, the dampness of the space is already working against them. One thickly sprayed painting has simply never dried. The curators said they thought the painted works could last two or three decades if left untouched. But even assuming the work is discovered by the transportation authority sooner than that, PAC said, “I like the fact that it’ll feel apocalyptic, because things will be deteriorating, and it’ll already be a memory.”

After this reporter’s tour, the curators destroyed the equipment they had been using to get in and out of the site. “We’re not under the illusion that no one will ever see it,” Workhorse said. “But what we are trying to do is to discourage it as much as possible.” He stressed that any self-styled explorer who found the site and attempted to enter it would be taking a real risk.

“If you go in there and break your neck, nobody’s going to hear you scream,” he said — at least assuming there are no track workers around. “You’re just going to have to hope that someone is going to find you before you die.”

For a larger read on the story please refer to NYT article.